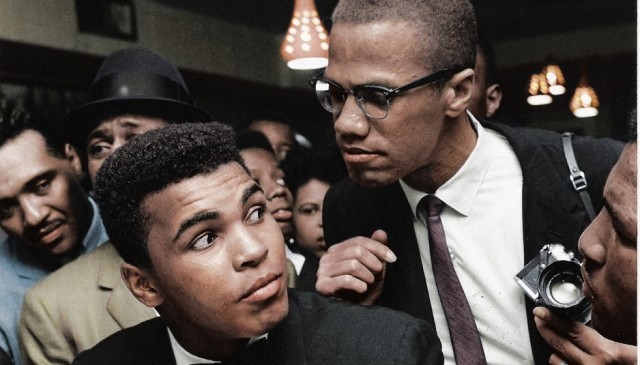

Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X

A major sticking point in the Coates-West feud was the discussion of Barack Obama and Malcolm X in We Were Eight Years in Power. Given the chapter on Malcolm in Between the World and Me, I anticipated a thought experiment exploring what would Malcolm say about Barack Obama’s presidency. While that didn’t happen, after Cornel West published his bombastic critique, many Black intellectuals weighed in. And there were a lot of Malcolm references to talk about Malcolm’s internationalism, his critique of power, and even critiquing West for hanging out with Malcolm’s rival, Louis Farrakhan. Yet, all of these references failed to explore Malcolm #BeingBlackandMuslim and what did that mean during the Obama years. While valorizing Black Muslim heroes like Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X in their death, mainstream Black civil rights leaders, public figures and even activists act as if we are historical footnotes. We’re still here. Black American Muslims in Detroit, Minneapolis, Boston, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles were targeted by harmful policies during the Obama administration. We still are targeted, but our plight is often erased in Black spaces.

How do we write a whole book about Executive Power without talking about how that power was weilded against Black and Brown bodies in the U.S. and abroad? It’s a legit question that Muslim Americans had and one reason why aspects of West’s critique resonated with many us. During Obama’s administration there are segments of Black America that were subject to similar COINTELPRO policies that helped create the conditions for Malcolm’s assassination. It was during the Obama administration when imam Luqman Abdullah was killed by federal agents. Only the local Boston chapter of Black Lives Matter brought attention to Usaama Rahim’s killing. Often, when high profile Black activists, even radical ones, talk about Muslims they imagine they are talking about people “over there” or immigrants. Yet, one third of American Muslims are Black and we are especially targeted by National Security system and criminal justice system.

Given that climate of entrapment, career damaging investigations, and public drudging, many Black Muslims were highly critical of the Obama administration. Yet his symbolic victory was not lost on us. Nor was it lost on those of us who were invited to the first and likely last 2016 eid celebration at the White House that was hella Black.

#BlackOutEid

COINTELPRO is not a historical concept when you have informants in our spaces of worship, volunteering for your organization, and FBI agents showing up at your trainings. Nor is it a that far off when you have your whole community fighting about a partnership with DHS to investigate your own community. Drones and bombings are not an abstract concept when you have to comfort a mentor whose families members were obliterated by US made missile. Nor is the no fly list a abstract issue, when your key participant is detained at an airport and misses their flight to your event. Rendition or secret detention is not just a political thriller when you’re at a baby shower hugging a wife whose husband was disappeared in a foreign prison. Dr. Su’ad Abdul Khabeer reminds us, we Black Americans need to contend with our relationship with empire. She had a simple but powerful letter to deliver to Obama that day.

We have to look at the tools and tactics that the main beneficiaries of white supremacy use to maintain their advantaged position. Sometimes, we are its tools. Just as we suffer in this country, we cannot turn away from the collateral damage of white supremacy. They are the undocumented laborers, the Black and Latino kids pipelined into prison, the indigenous people fighting for sovereignty and environmental sanctity. There are many who are getting crushed in the systemic mechanism, and it is not accidental. Their sweat, tears, and blood are being used as a lubricant for the gears to work together. If we cannot find another social lubricant, other than suffering, for the gears to move, then we must build better social mechanism that renders white supremacy irrelevant.

If Black public intellectuals are going truth tellers shining light on White Supremacy to massive audiences, then their light needs to multipronged and not cast those of us at the intersections into the shadows. This is why much of my focus last year was in making the connections. I sought to explore the ways in which the criminal justice system, immigration system, and national security system targets Black Muslims by bringing together organizers from Undocublack Network, Black Alliance for Just Immigration, Prison Education Project, Black Liberation Project, Partnership for the Advancement of New Americans (PANA), and more. I’m hoping that in 2018 Black kinfolk can work together more. I’ve been reaching out for the past few years, and I’m hoping that some of y’all respond to my call because we need our kinfolks now more than ever.