On February 5th, Muslim twitter responded to the Right Wing backlash over Obama meeting with Muslims leaders with hilarious tweets #MuslimMeeting. Although many of the tweets were light hearted, others were critical of the meeting largely due to its secrecy. “We want to know who attended the meeting?” While Dean Obeidallah released his statement right away, organizations such as American Muslim Health Professions, Muslim Advocates, and Muslim Public Affairs Council released separate statements. The White House issued a statement saying that “Among the topics of discussion were the community’s efforts and partnerships with the Administration on a range of domestic issues such as the Affordable Care Act, issues of anti-Muslim violence and discrimination, the 21st Century Policing Task Force, and the upcoming White House Summit on Countering Violence (sic) Extremism.” Despite the controversy on social media, numerous people noted the unprecedented gender and ethnic diversity of the meeting once all the attendees were identified.[1] And within that diversity, African-American or Black Muslims addressed their community’s concerns in a space where they had historically been excluded.

While diversity is often dismissed as a politically correct catchword, the lack of diversity in representation and opinion within the Muslim community when it comes to representing our collective concerns to administrative bodies has had a troubling effect on Black and Latino communities. A salient example of this is the pervasive CVE programming that has been created by Muslim organizations.This programming has ignored the complex and difficult history that Black and Latino communities have had faced with law enforcement and created a new set of mechanisms to criminalize and marginalize these communities.

The US government has reduced its engagement with the Muslim community and increased focus on Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) programs. By internalizing the security framework, Muslims are undermining their own empowerment and overlooking important lessons from our past. CVE programs arise from the 2007 Implementation Plan for Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States (SIP.) According to Bloomberg ”A pilot program in the Department of Justice that started in mid-2013 sought to forge links between law enforcement and Muslim communities in Boston, Los Angeles and Minneapolis. Best practices from those three cities will be discussed at the summit later this month.”[2]

While CVE programs may not be not nefarious in and of themselves, they represent many converging forces on the Muslim American community. The framing asks Muslim Americans to adopt the Islamophobic rhetoric where the good Muslims need to confront the bad Muslims. Haroon Manjlai, Public Affairs Coordinator of Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR-LA), explains, “Given the potential of CVE program to impact first amendment freedoms and protected activities and it’s potential of criminalizing the Muslim Community as being is a cause for concern and is something that CAIR does not agree to and sign off.”Kameelah Mu’min Rashad, Founder of Muslim Wellness Foundation and University of Pennsylvania Muslim Chaplain who had attended the closed door meeting with the President discussed her concerns about the CVE programs. Pointing to Black American Muslims distrust of these types of program, she said:

We come with more skeptical born of historical reality. We come to these programs, asking how do these programs do damage to our community. There are people who are watching and reporting back to the government, we are very ambivalent about the stated goals of these types of programs.

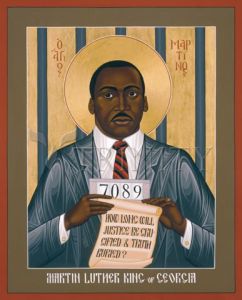

For many Black American Muslims, CVE programs reminds them of the actions of COINTELPRO (an acronym for Counter Intelligence Program), a program conducted by the FBI against civil rights leaders including Dr. Martin Luther King, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Nation of Islam, and the Black Panther Party. TIn essence, NAACP, Martin Luther King, NOI, and Black Panther Party challenged the status quo system of white supremacy. In the context of Muslim Americans, Black History is our history. The intended effect of these programs included the following:

- create a negative public image

- break down internal organization

- create dissention between groups

- restrict access to organizational resources

- restrict organizational capacity to protest

- Hinder the ability of targeted individuals to participate in group activities,[3]

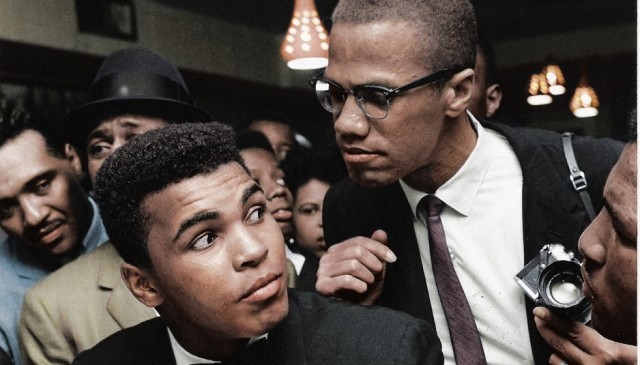

As Rashad points out that organizations aligning with CVE might not “recognize how programs just like this have been used to undermine self determination and self identity of a community.” This has led to ambivalent feelings about the government and law enforcement agencies. Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X’s FBI files provide some insight into the extent of surveillance.[4] It should be remembered that Malcolm X did not grow up in a vacuum, as his father who was a follower of Marcus Garvey met an untimely death and the US government worked to undermine Black self determination, from the time of Marcus Garvey to the Black Panther Party. Thus, these suspicions are not unwarranted. Black American Muslims have good reasons for looking at CVE programs not as partnerships between government and Muslim communities, but mechanisms of control. Yet, violent extremism seems to be the only platform that some Muslim groups are gaining traction in DC. This is causing further fragmentation within the American Muslim community along racial lines.

Muslims and non-Muslim activists and civil liberties groups are concerned about the security framework for Muslim engagement with the government. Local and Federal law enforcement agencies often do not approach the Muslim American community outside of issues of national security or foreign policy. In essence, Muslims are criminalized and deemed foreign. Such approach also marginalizes the Black Muslim community and creates a dichotomy, which was applied during the colonial period: the good Muslim versus the Bad Muslim.

From a civil liberties perspective, Counter Violent Extremism programs and the Security framework is deeply troubling. The unease is especially tangible as Muslim Americans are still waiting for the decision of the appeals case is considering constitutionality of NYPD’s spying program, which targeted Muslim Americans simply for their religion. Although LAPD did not take the same measures as the NYPD in spying, the Suspicious Activities Reporting (SAR) program has raised similar concerns amongst civil liberties groups,such as the ACLU. Based on the type of activities falling under Suspcious Activity Reporting (SAR) individuals doing simple things such as taking pictures or asking directions can come find themselves under state surveillance.

This is exactly what happened to my husband Marc Manley while he was student at Temple University and Chaplain of UPenn. He took a picture for an art class, which resulted in the Philadelphia Police department and Southeastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority (SEPTA) police detraining, searching and questioning him. A few days later two FBI came to his job. After talking with some friends, he contacted the American Civil Liberties Union, which provided a lawyer who was present in the meeting with two FBI agents. and asked him questions about his ethnicity, origins, where his parents were from, notably they asked whether he was of a Middle Eastern background. Following that initial meeting, then the FBI wanted to establish a relationship with them as a chaplain to work cooperatively as Chaplain of University of Pennsylvania. He stated, “It was never clearly stated about what that meant.”

According to the LA Times, the Obama administration has chosen LA as one of the pilot programs for CVE. I spoke with Garrison Doreck, a PhD student at Irvine who has worked on Muslim Rights, Mapping programs, and civic engagement. He attended a series of law enforcement outreach meetings as a participant observer. He explained that they were a series of public forums where the LAPD goes to different mosques to address various issues or themes. These meetings are powerful junctures where the community can voice their concerns, all the while feeling the watchful eye of the government. In October 2014, Sahar Aziz argued that these meetings could be intelligence gathering opportunities. While Aziz pointed to the profiling of Arabs and South Asians, increasingly Black American Muslims are under suspicion. Doreck pointed to the Suspicious Activity Reports (SAR) audits, highlighting some of the racial disparities. Although Muslim groups in Los Angeles have pushed for more reform, the suspicions have shifted away from immigrant Muslims and increasingly towards Black Muslims, who are now disproportionately the subject of Suspicious Activity Reports.[5]

This points to Several prominent Black Muslim community leaders, have called for Muslim advocacy groups in DC to be more representative of the diverse Muslim American population. So when MPAC gave Michael Downing an award, it reflected that disconnect with the Black and Latino community who were still reeling from police killing of Ezzel Ford. The petition that ciruclated before the event prompted MPAC to create hold a “Let’s Be Honest”panel at the MPAC 2014 conference moderated by Jihad Turk, and featuring Jihad Saafir, Hind Makki, Marwa Aly, Rami Nashashibi, and Khalid Latif. Many, have pointed to MPAC’s tone deaf choice for MPAC to name its CVE “Safe Spaces.” Safe space is a term where a marginalized group does not “face standard mainstream stereotypes and marginalization” or people with shared political and ideological stances can express themselves openly. By being asked to report “Suspicious Activities,” this means that Muslims are supposed to internalize the CVE and report on each other.

Black American Muslim leaders are asking the government to stop viewing Muslim Americans as a problem, but as partners because many Muslim communities are involved in alleviating poverty, reintegrating the formerly incarcerated, recovery programs such as Milati IIlami., which is a 12 step program to support Muslims recovering from substance abuse. Muslim advocacy groups should promote policies that reflect Muslim American interests, and not just foreign policy or counter violent extremism. One example is ILM, a human development organization focusing on building “self-worth” through various humanitarian projects. ILM’s executive director Umar Hakim told me, “If we start where Malcolm X left off and gain political voice, we are going to have to start dialoguing to begin understanding one another, we need to identify each others’ self interests”

Like others, Hakim stated that he would like to see Muslim advocacy groups engaged in Law enforcement outreach programs address police brutality and the Black Lives Matter movement. Black Lives Matter movement was created in 2012 after Trayvon Martin’s murderer, George Zimmerman, was acquitted for his crime. The organization works to resist the de-humanization of Black Americans. Social justice groups have pointed to the criminal justice system and the mass incarceration of Black Americans. Many have pointed to how the criminal justice system disempowers formerly incarcerated individuals, depriving them of rights to vote or receive assistance for education, in addition to a record that creates barriers to education. In California, activists worked on a Proposition 47 that passed this November, which made 6 non-violent felonies into misdemeanors. In addition to alleviating barriers to reentry in society, the programs save the state approximately $150 million to $250 million per year which would go to Safe neighborhoods and school. Marcus Allgood, a community activist who was theProposition 47 team captain in South L.A , noted that although Black Muslims are disproportionately affected by racial and religious profiling they receive little support. He said, “The consensus is that when it comes to the issues of social justice, we don’t see the participation of Muslims at all.” Marcus explained that it was the Quran’s message of social justice that attracted him to Islam. He noted, “Yet, the imams in the local LA community were hard pressed to show their support.” Allgood explained after a lot of phone calls and discussions, many slowly became on board. This past week, he saw some progress:

I was just dealing with CAIR, they came to ACLU and 10 organizations including members of Black Lives Matter who were interested in dealing with definition of racial profiling trying to get LAPD to have a definition aligned with DOJ on their definition. We are working on drafting a bill with Senator Weber.

Hakim, Allgood and Rashad point to the need to address the conditions that cause the radicalization or destructive patterns in multiple groups. While people have looked to Islam as the problem or Black and Latinos as a problem, the very same conditions cause disaffected white men to join hate groups or become involved in drugs and gangs as well.

The PhD student, Doreck explains, “ the Muslim community has been put in a security box since the mid 90s with the 1996 secret evidence act and of course after 9/11. How do you break out of that box? Or, how do you broaden the discussion? There are muslims interested in education and health care that affect their lives more.”

Kameelah Mu’min Rashad hoped that Muslim national organizations followed Black American Muslim approaches to civic engagement and social justice work. She explained “The government engagement, civic work, and community involvement is different, the reach of Black Muslims usually extends to the community regardless of faith,” Umar Hakim affirmed this sentiment, pointing out that he is not just concerned about social justice as it relates to Muslims, but to the broader society. In other words, Muslim social justice issues should broaden to not just focus on Muslim specific issues, but issues that improve the overall conditions in society.

Manjlai of CAIR stated based on previous CVE discussions, meetings with Secretary Johnson, Department of Homeland Security and FBI, CAIR anticipates that the program which will be announced on February 18 CVE summit to have the same problematic aspects, exemplified by the infamous questionnaire which asks Muslims to rate families at risk of raising extremists. He said, “we are going to be proactive with masjid boards and community leaders to educate them on what CVE is and its potential impact on our community.”

The most important lesson learned from the Muslim meeting is that the Black American participants pointed to ways in which the government can engage with Muslims as partners in addressing social justice issues. Focusing on local efforts, Muslims have the most potential for change. Also centering Black/African American Muslims in this conversation is also critical to achieving a shift in civic engagement. One such issue is racial profiling, police brutality, and the Prison Industrial Complex. Muslim Americans must come together and take a stand, make a statement about 21st century policing in support of #BlackLivesMatter. We need our Muslim stakeholders, including imams, grassroots organizers, concerned citizens, community leaders, and civil service workers, to come together, create a roadmap, build coalitions and engage in a meaningful way. As national organizations such as CAIR and Muslim Advocates become more aligned with grassroots work against racial and religious profiling, they can become more inclusive, effective, and responsive to our community’s needs.

[1] http://www.isna.net/isna-president-at-the-white-house.html ISNA writes that the members who attended inclued: Dr. Sherman Jackson, the King Faisal Chair of Islamic Thought and Culture and Professor of Religion and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California (USC), Farhana Khera, president and executive director of Muslim Advocates, Imam Mohamed Magid from All Dulles Area Muslim Society (ADAMS) and former president of ISNA, Arshia Wajid, founder and president of American Muslim Health Professionals (AMHP), Hoda Elshishtawy, the national policy analyst for the Muslim Public Affairs Council (MPAC), Farhan Latif, chief operating officer and director of policy impact with the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), Maya Berry, executive director of the Arab-American Institute (AAI), Palestinian-American comedian Dean Obeidallah, Rahat Hussain, director of legal and policy Affairs with Universal Muslim Association of America (UMAA), Diego Arancibia, Board Member and Associate Director of Ta’Leef Collective, Kameelah Mu’Min Rashad, Muslim Chaplain at the University of Pennsylvania and Founder of the Muslim Wellness Foundation,and Bilqis Abdul-Qaadir, a graduate assistant with Indiana State University’s women’s basketball team who played basketball while wearing the Islamic headscarf.?

[1] http://www.isna.net/isna-president-at-the-white-house.html ISNA writes that the members who attended inclued: Dr. Sherman Jackson, the King Faisal Chair of Islamic Thought and Culture and Professor of Religion and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California (USC), Farhana Khera, president and executive director of Muslim Advocates, Imam Mohamed Magid from All Dulles Area Muslim Society (ADAMS) and former president of ISNA, Arshia Wajid, founder and president of American Muslim Health Professionals (AMHP), Hoda Elshishtawy, the national policy analyst for the Muslim Public Affairs Council (MPAC), Farhan Latif, chief operating officer and director of policy impact with the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), Maya Berry, executive director of the Arab-American Institute (AAI), Palestinian-American comedian Dean Obeidallah, Rahat Hussain, director of legal and policy Affairs with Universal Muslim Association of America (UMAA), Diego Arancibia, Board Member and Associate Director of Ta’Leef Collective, Kameelah Mu’Min Rashad, Muslim Chaplain at the University of Pennsylvania and Founder of the Muslim Wellness Foundation,and Bilqis Abdul-Qaadir, a graduate assistant with Indiana State University’s women’s basketball team who played basketball while wearing the Islamic headscarf.?

[2] http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-02-05/white-house-woos-american-muslims-as-obama-hardens-stance

[3] Mathieu Deflam (2008). Surveillance and governance: crime control and beyond. Emerald Publishing Group. pp. 184–185

[4] With the controversial claims that law enforcement agencies knew of the plot to assisiinate Malcolm X, but did not intervene, there is a petition to open his FBI files and remove redactions. http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2000-05-14/news/0005140182_1_malcolm-x-kill-malcolm-muhammad; http://baltimoretimes-online.com/news/2014/dec/26/petition-launched-open-federal-files-malcolm-x/

[5] http://www.lapdpolicecom.lacity.org/031913/BPC_13-0097.pdf