Originally published on Medium

I stepped to the podium, and in front of an audience of world-famous researchers, scholars, and academics, I nervously opened my first conference paper by sharing my pre-9/11 experiences as a Black American Muslim college student. I wrote this paper without access to archives or even many journal articles. However, I had scores of personal histories, pop culture references, and news headlines. I used those sources to outline how Islamophobia and anti-Black racism overlap, causing notable racial disparities in the criminal justice, immigration, and national security systems. Black Muslims are often considered dangerous, illegitimate, rigid, violent, and promiscuous. When we analyze the tropes used to describe Black Muslims, we can see that the systemic oppression of Black Muslims is rooted in centuries-long discourses and policies.

Whether through the lens of service or crime, Black Muslims face particular vulnerabilities. Over the past 15 years, there has been a growth of literature on the impact of Post 9/11 policies and systemic racism on Black Muslims. Dr. Su’ad Abdul Khabeer writes about the two facets of the facts of blackness: disavowal and instrumentalization. Black culture is seen as immoral or blackness is used as a tool of resistance. In her exploration of 100 years of Muslim tropes in film Dr. Maytha Alhassen writes that Black Muslims are framed as either haters or redeemers. Both scholars point to how the production of knowledge about Black Muslims reinforces stereotypes and marginalization.

While I knew that Black Muslims experienced Islamophobia differently, it was not until I wrote that paper that I could name our experiences. I found several tropes circulating in reports, blog entries, and articles, including Burqa Bandit, Jailhouse Jihadi, Counterfeit Akhi, Somali Shabab, and Militant Muslim. In 2015, I learned that I lived in a pilot city for Counter Violent Extremism programs and found racial disparities in Suspicious Activity Reports. After I wrote my article in the Islamic Monthly, civil liberties organizations, including the ACLU, Center for Constitutional Rights, and CAIR reached out to work with me for programming and education resources. I learned that West African and East African communities were particularly vulnerable. While the literature on the criminalization of Black Muslims was sparse, I took my initial research to write op-eds and turned them into a conference abstract. My creative writing professor advised us to steer clear of tropes. But after meeting Zienab Abdelgany, an organizer at CAIR Greater Los Angeles who introduced me to the Knowledge Power Chart, I knew starting with anti-Black tropes to mapping out the criminalization of Black Muslims would be an effective strategy.

The ways that we think about people often justify their treatment or conditions. Dominant narratives can come from stereotypes, commonly held beliefs, or tropes. Anti-Black Islamophobia has deep roots in Arabic literature and western Orientalist art and literature. A trope is a powerful image, and it is an overused device that obscures truth. Blackamoor is a European visual trope of decorative art in furniture, jewelry, and paintings. During my travels in Egypt, I saw Blackamoor art left an imprint in colonized Southwest Asia and North Africa with a brass relief of a bare-chested Black woman on my landlord’s foyer and an orientalist painting depicting a Black woman scrubbing a white woman. They reinforced a racialized regime of Black people as servile and sexually suggestive.

Dehumanizing tropes don’t have to come in the form of slurs. Sometimes it can be in canonization. Black Muslims can take on saintly roles as martyrs, servants, wetnurses. And the modern iterations are the magical Black girl or Black woman savior (I will discuss these tropes in politics and science fiction). Four tropes help us better understand the systemic oppression of Black Muslims: the Magical Negro, Holy Hustler/Whore, Militant Muslim, and Muslimah Mammy.

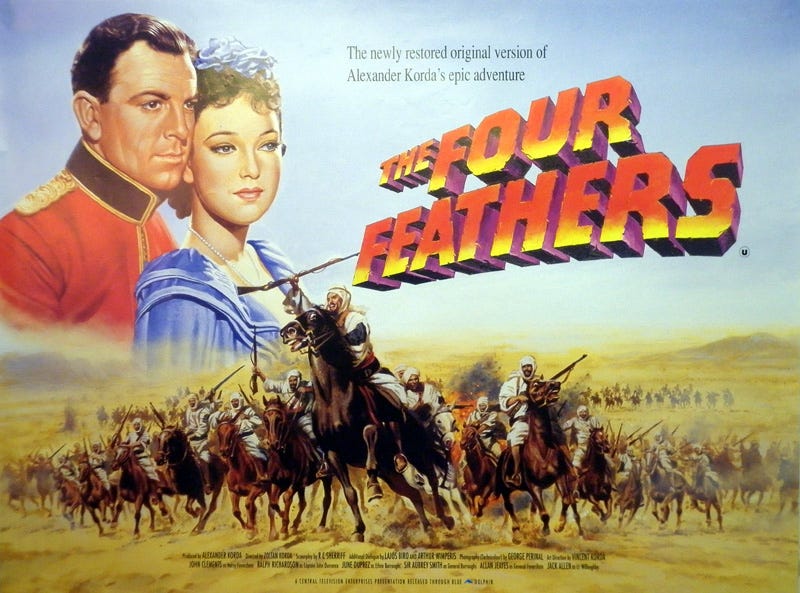

Magical Negro- The Magical Negro is a black character who is a wise mystic. Black characters often only exist to move the plot along by advising non-black characters with some esoteric wisdom. They may even have some special power or insight due to their status on the margins of society. Orientalist painters depict Black musicians or magicians. French and British colonial scholars and administrators also framed Black Africans as inherently superstitious, with an Islam that is corrupted by African practices. The Black Muslim version of Magical negro is often tied to mysticism, but not in the Rumi or IbnArabi way. Those are too scholastic. Instead, the Magical Muslim Negro is tied to suspect practices tied to animism or jinn. They may be the voices calling to prayer, but not the scholar. The Magical Black Muslim is often musical and mystical in film and popular culture. In many Muslim societies, descendants of Africans trafficked in the trans-Saharan or Indian ocean slave trade maintain some distinct spiritual practices. Religious syncretism and musical performances are often the only aspects of their cultural practices that ethnographers feature. Further, due to the marginalization of Africans in the Diaspora in the Mediterranean or South Asia, their role in society is often limited to serving as spiritual mediums often through music.

Holy Harlot/Hustler- These are two sides of the coin, as the hustler and whores are associated with illicit activity. Orientalist paintings feature turbaned Black men as pimps in slave markets. The Holy hustler corrupts society by selling sex. Either the virginal captive white slaves, an obsession in Orientalist paintings or tempting white men with corruption by selling a dusky venus. Colonial reports often called Black Muslim leaders as charlatans and tricksters. Another variation is the street preacher or vendor selling wares or incense in inner cities. The Black Muslimah Hustler is suspect because she has to leave her household to make a living. Historically, Black women’s femininity was not something to be protected or saved, unlike Brown women. Black Muslim women are not considered delicate feminine and deserve support and protection. When she demands respect in this gig economy for her work ethic, she is called a diva, which Beyonce tells us is another word for a hustler. The Black Jezebel trope has been used in western societies to depict Black women unrapable. In the SWANA region, Black women of all faiths experience the brunt of hyper-sexualization, rape, and African migrants are raped and trafficked into the sex trade.

Militant Muslim. In Alexandre Dumas’s Count of Monte Cristo, Ali is an enslaved Nubian weapon master who also happens to be mute. Numerous orientalist paintings show Black warriors trampled upon by Matamoros (the killer of moors), fanatical troops, or as harem guards. Today, Black militant Muslims are revolutionaries who rail against the man. The militant Muslim is maladjusted, out of touch, and angry. During the interwar period in Northern Nigeria and Sudan, colonial authorities wrote about the fanaticism of Black Muslims. They believed that their racial makeup made them more prone to violence. The documentary The Hate that Hate Produced (1959) caused hysteria. Black Muslims that critique white supremacy are often framed this way. The only reform for the militant Muslim is the acceptance of the status quo and embracing Christianity.

Muslimah mammy– In contrast to the holy whore, the Muslimah mammy is desexualized and non-threatening. Instead, she represents the permanent servitude of Black women to society’s whims. The mammy is a matronly figure who is the caretaker of others outside her household. She likely has to neglect her immediate family in service to white women. She cares for children and is known for their loyalty and selflessness. Orientalist paintings often depict Black women as servants in harems. Black women elders, especially African American Muslim women, are not respected for their experience, given titles in deference to their status and wisdom. Due to economic pressures, women of the African Diaspora migrate to Southwest Asia, North Africa, and the Gulf for work. They are often relegated to domestic work, even if they have various skills. Further, the kafalah system a rife full of exploitation. The Muslimah mammy in US contexts often overlaps with how Black mothers are depicted as domineering emasculators or saintly servants. Black women may be school teachers, nonprofit workers, or advisors with little institutional power. Instead, a Black Muslimah mammy is the caretaker of the people who benefit from institutions and systems of power.

I aim to explore these tropes further in the coming months as they intersect with popular culture. Whether intentional or unintentional, the perpetuation of these tropes continues to cause harm. Tropes minimize Black Muslims’ full humanity, contributions, and aspirations. It makes the world especially unsafe for Black Muslim women, even for one who runs an anti-racism organization. This is only the beginning of my exploration and contribution to the field. I push back against the boxes people try to put me in, whether they be the dusky venus, the sapphire, jezebel, or mammy tropes. We must interrogate these tropes and unpack how they appear in our daily interactions. By countering these tropes, I reclaim my story. Black Muslims are not objects but protagonists in our own stories.