Why is it that every khutbah, every lecture, and every conference plays out more like a pep rally where we are mere spectators and fans, instead of the players who should be training and practicing for the big game? And we keep wondering why our team is losing. That’s because none of us are in shape, we can’t decode the playbook, worse, we don’t know how to land that shot. Okay, I’ll stop the sports metaphor because I was never good at team sports. The whole point is that our community life is not necessarily helping us truly transform, improving our conduct and living good, wholesome, and happy lives. What constitutes happiness and a good life is an ancient question and people have come up with different answers. But the most consistent in their views have been philosophers and religious thinkers. Even during the ancient period, both have agreed that living a good life entails living a life of virtue. A virtuous life is not just about the ability to follow a rule book or perform rhetorical dexterity to find legal loopholes to justify our means to that end. The dominant approach that Muslims have taken towards virtue is the rule book or laundry list approach. However, this approach is often self-defeating, making us focus on the virtue without exploring what’s wrong with us. This is the same approach that Muslims take to the sunnah, where we focus on traditions and practices that appeal to us, hoping to be cured of certain ills. Often, we are treating mere symptoms, rather than curing the disease. It is time we begin a holistic approach to bettering ourselves, treating both the symptoms and eradicating the diseases that are destroying the quality of our own lives and our community life overall. Moral and personal development should be the focus of living a virtuous life or good life. Living a good life is based on universal principles that we find in Islam, as well as many other faiths. There are many tools to achieve that end, many found in Islam, but also wisdom that we can draw from ancient sages, philosophers, and even insights from our own society. We should not ignore any tool that can help us with personal mastery.

While many Muslims are concerned with righteousness, we seem to be confused about what does that truly mean. And this is why we should begin to think about virtue and ethics to understand the big picture or (كلٌيات). Before we begin throwing around the term virtue and ethics, let’s first look at what do these terms mean:

vir·tue [vur-choo] –noun

1. moral excellence; goodness; righteousness.

2. conformity of one’s life and conduct to moral and ethical principles; uprightness; rectitude.

3. chastity; virginity: to lose one’s virtue.

eth·ics [eth-iks] –plural noun

1.( used with a singular or plural verb ) a system of moral principles: the ethics of a culture.

2.the rules of conduct recognized in respect to a particular class of human actions or a particular group, culture, etc.: medical ethics; Christian ethics.

3.moral principles, as of an individual: His ethics forbade betrayal of a confide

As I stated earlier, religious thinkers and philosophers have mulled over virtue and ethics for thousands of years. Socrates dedicated the latter part of his life to the investigation the development of moral character. Plato recounts a dialogue that Socrates had with Meno about the nature of virtue. Meno asks Socrates whether virtue can be taught, whether it is something that someone can practice, or whether it is something that someone is born with. Socrates believed that there was a link between virtue and knowledge. Only, he believed that people aren’t taught things, they simply remember what their soul had forgotten. If this gets confusing, just remember that Socrates believed that the soul was immortal and that people were born over and over again. Therefore, they just had to remember what they knew before. But, let’s ignore this part of his philosophy and focus on his idea that in order for someone to be virtuous, that person has to have sufficient knowledge. Two arguments that back this up are as follows:

- All rational desires are focused on what is good; therefore if one knows what is good, he or she not act contrary.

- If one has non-rational desires, but knowledge is sufficient to overcome them, so if one is knowledgeable of goodness, he will not act irrationally. [7]

Socrates believes that no rational person would act in a way that was harmful to his/herself. Maybe people are mistaken in their knowledge? I guess Socrates didn’t account for atrocities like the Holocaust or Rwandan genocide. Harming someone else destroys our own humanity. So moving on to the next group of Hellenistic thinkers. The Stoics were sort of the inheritors of Socratic views on rational thought and virtue. They believed that human beings by nature were rational animals, and therefore it was natural to live “the life acording to reason.” Virtue was excellence and according to the divine law of the cosmos. John Stobaeus the following as stoic goals in life:

- Zeno: living in agreement

- Cleanthes: living in agreement with nature

- Chrysippus: to live according to the experience of the things that happen by nature

- Diogenes: to be reasonable in the selection and rejection of natural things

- Archedemus: to live completing all the appropriate acts

- Antipater: to live invariably selecting natural things and rejecting unnatural things

Stobeaus goes on to define the four main virtues of the stoics:

Prudence: (concerns appropriate acts) knowledge of what one is to do and not to do and what is neither

Temperance: (concerning human impulses) knowledge of what is to be chosen and avoided and what is neither

Justice: (concerning distributions) knowledge of the distribution of proper value to each person

Courage: (concerning standing firm) knowledge of what is terrible and what is not terrible and what is neither. [8]

These are all reasonable enough and can be found in many traditions, but who would like to live like a stoic, unaffected by passions or hardships? I suppose a lot of people, which is the appeal of Zen Buddhism for many people. Without going in uncharted waters (at least for me), let’s move on to the lineage of philosophy and ethics within Muslim traditions.

Socratic thought profoundly influenced medieval Muslim philosophers, the Muatazilites. But I won’t go into the controversies surrounding their philosophical school, especially in their argument that one can derive God’s laws without revelation. Instead, I bring them up to point out that in using their Greek influenced dialectical methods, scholars like Imam Ghazali were able to safeguard and in many ways revive Islam. The strength of Islamic institutions and thought was in applying universal Islamic principles to local institutions or cultural forms to produce something that was relevant in societies across the globe and over 1400 years. But since Imam Ghazali was so successful in shutting down the philosophers that very few Muslims have ventured back in the territory of exploring virtue through reason, and not just solely from revelation and hadith traditions. The unfortunate consequence is that we are back to the laundry list approach to dealing with virtue in Islam. We are a community concerned with ethics, but without an ethical system.

A few western scholars have approached Azhari scholars over the need to consider ethical systems. Some of the traditional scholars were amenable to this idea, but perhaps we all lack the training in performing the task. That doesn’t mean that we can develop the requisite skills, especially with some effort. I think this would be a fruitful direction to go in because over the past few years, I have often wondered how is that many religious people can do things that are harmful to themselves and others, but still consider themselves moral and receive no censure by the religious community. In many conversations with friends, peers, and loved ones, the answer came to the lack of a consistent ethical system. The basic assumption is that if something is allowed in Islam that it is the right thing to do at any given point in time. People often overlook the question of whether something was right in one given circumstance could be wrong in another, and what guiding principles should we draw upon to determine a proper course of action. The salad bar approach to the religion undermines holistic development and moral consistency. Further, many adherents have used Islam to justify their own shortcomings, in effect deluding themselves with self righteousness. This is how we have people hiding behind, beneath, and under the guise of religion.

Recalling Socrates, I do think that even though many Muslims rejected the Greek influence in Muatazilite thought, they still seem to be influenced by his intellectualism. Tariq Ramadan writes:

Islamic literature is full of injunctions about the centrality of an education based on ethics and proper ends. Individual responsibility, when it comes to communicating, learning and teaching is central to the Islamic message. Muslims are expected to be “witnesses to their message before people”, which means speaking in a decent way, preventing cheating and corruption, and respecting the environment. [9]

Muslims are obsessed with knowledge and knowing. We love books, classes, lectures, debates, pamphlets, websites, forums, podcasts and blogs that make us feel knowledgeable. The assumption is that correct knowledge leads to better practice. The problem is that true knowledge is not just limited to thought or reason. But knowing how to act sometimes takes practice and constant strength training.

If you want to really know how to play basketball, you can’t just read a bunch of books. You have to get on the court, practice making shots, until your hand-eye coordination has figured out how to make that perfect arch to land the shot. At first, you must be very conscious of each action, how to dribble, how to pass, rebound, and with time things come natural. So, while Socrates believed that knowledge was the key to virtue, virtue actually comes from something you practice over and over again until you get it right. Of course, knowledge is essential, but one has to inculcate that knowledge so that we embody it. Action is essential in applying that knowledge. This is why Muslims perform salat, fast, go on hajj and are reminded to constantly perform remembrance. These actions reinforce the declaration of faith. And we do all of those things to achieve one important goal, pleasing our Lord.

You must be aware of the goal you are aiming, so that when you miss the shot you understand what you did wrong. If you have no knowledge of your goal and are unreflective, then you will keep making that same bad shot over and over. I admit, I slipped back into the sports metaphor and, honestly, I was never good at basketball. I’m a sore sport, but I have trained and gotten in shape for different reasons. Over the years, I have some modicum of self-discipline because of my deep commitment to self-development. I believe in setting goals. As Muslims, we should be aware of what our true goal is, and that is to be successful in this life and the hereafter. Outside of Imam Ghazali’s account of his spiritual crisis, I haven’t found too many detailed stories of how individual Muslims conquered their own shortcomings. So, I turn to my own cultural context to see who has developed systems of personal development, especially focusing on moral development.

Benjamin Franklin comes to mind not because I live in Philadelphia and there are statues of him everywhere, but rather because he created a self improvement program long before the self-help craze of the late 20th century. Franklin’s list of virtues and his efforts to gain mastery over them are an interesting case study. Franklin listed thirteen virtues that he considered to be the most important and they are as follows:

1 . Temperance. Eat not to . not to Elevation.

2. Silence. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself.Avoid trifling Conversation.

3. Order. Let all your Things have their Places. Let each Part of your Business have its Time.

4. Resolution. Resolve to perform what you ought.Perform without fail what you resolve.

5. Frugality. Make no Expense but to do good to others or yourself: i.e. Waste nothing.

6. Industry. Lose no Time. Be always employ’d in something useful. Cut off all unnecessary Actions.

7. Sincerity. Use no hurtful Deceit. Think innocently and justly; and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

8. Justice. Wrong none, by doing Injuries or omitting the Benefits that are your Duty.

9. Moderation. Avoid Extremes. Forbear resenting Injuries so much as you think they deserve.

10. Cleanliness. Tolerate no Uncleanness in Body, Clothes or Habitation.

11 . Tranquillity.Be not disturbed at Trifles, or at Accidents common or unavoidable.

12. Chastity. Rarely use Venery but for Health or Offspring; Never to Dullness, Weakness, or the Injury of your own or another’s Peace or Reputation.

13. Humility. Imitate Jesus and Socrates.

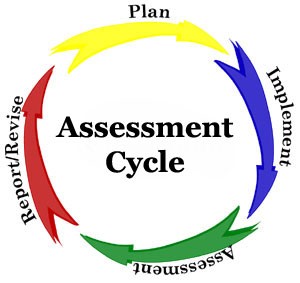

The thing that made Franklin so important in this area was his effort at tracking his progress on these virtues, with the aim of mastering each one. I think it is important to note how self-reflexive he was in this process. This was all about personal accountability. At the end of the day, he’d do an inventory of his actions. If he violated one of the virtues, he checked it off. Initially, he had a lot of check marks. But over time, the check marks became fewer and fewer. Eventually he gave up the keeping a daily log, but he continued the path of self-improvement throughout his life. For some, this may seem a bit OCD. But for others, it may be a useful tool in taking inventory of ourselves. There are even people today who have a similar chart on their iPhones. You can download the chart and some people have incorporated similar charts in self-help programs.

Now this takes us to the self-help industry. According to wikipedia, “the self-improvement industry, inclusive of books, seminars, audio and video products, and personal coaching, is said to constitute a 2.48-billion dollars-a-year industry [5]. Samuel Smiles coined the term “self-help” in 1882, in his book, Self-Help [4] While there are many controversies surrounding the self-help industry, and many valid critiques including the psycho-babble and placebo effect of some of the more dubious methods such as subliminal programming, there is great merit to self-improvement. People can transform themselves. One of the most powerful self-help programs, is Alcoholics Anonymous. The thing that I find very telling of their success can be found in the original Twelve Steps:

- We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable.

- Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

- Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

- Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

- Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

- Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

- Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.

- Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

- Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

- Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

- Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

- Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs. [6]

First, the admit that they don’t have control over the urges, they turn to a higher power for help, they take a serious inventory of their own shortcoming, repent and try to make amends to those whom they hurt. Importantly, through the constant process of prayer and correcting wrongs, AA members can have a spiritual awakening. In many ways this is a process of repentance that can be found in Islam: leaving the wrong action, making sincere repentance to our Lord for sinning against ourselves and Him, and asking forgiveness of another person if we harmed him or her. Repentance is a great blessing in Islam, it is an opportunity to experience Allah’s Grace and Mercy. Many people have achieved spiritual awakenings after a fall from grace.

Still a believer is not to be content with cyclical sinning. We are all taught the three stations of faith: submission ( Ihsan إسلام), belief (Iman إمان), and finally perfecting faith (Ihsan إحسان). Only through self-improvement and refining can an individual achieve Ihsan. Ihsan is the highest state of faith, where we live our lives knowing God can see us, even though we cannot see Him. This type of consciousness keeps us on our best behavior. But to have this consciousness at all times, we have to go through spiritual and moral development. In Islam, the method of spiritual development is called Purification of the heart, some calling it Tazkiyyah and others calling it Tasawwuf. Without going into the controversies surrounding Sufi/Salafi polemics, let us just note that the term tazkiyya has Quranic roots meaning to purify. Tasawwuf is a term that came later and is often associated with institutional developments in mystical brotherhoods. Still, the purpose was the same, to purify and improve the moral and spiritual standing of the adherent.

There are a great many virtues listed in the Quran. As pointed out earlier, many Muslims have created a laundry list of Islamic virtues. There is no shortage of literature on traits that Muslims should exemplify. And these are are beautiful and useful in improving ourselves. Muslim scholars are also concerned with what keeps Muslims from improving their station. Scholars, such as ibn Jawziyya and Imam Ghazali, have listed out several impediments to that refining process through tazkiyya or tasawwuf:

- Neglect or forgetfulness

- Submitting to one’s own passions (Nafs or Hawa)

- Shaytan

- Bad company or evil environment

- Arrogance or self-delusion

- Love of the material world

- Despair

Or they can be found in the four poisons of the heart.

- Excessive Talking

- Unrestrained glances

- Too much food

- Keeping Bad Company [3]

Sometimes that list of Muslim virtues is so long that an individual can feel very overwhelmed. Or we may think that avoiding one of the poisons or overcoming one of the impediments will cure us from a spiritual or emotional ailment. The list approach may blind us from looking at what is really wrong with ourselves. This is why I felt that it may be appropriate to try to consider some patterns that can give us a big picture approach. The Quran tells us:

Indeed, the Muslim men and Muslim women, the believing men and believing women, the obedient men and obedient women, the truthful men and truthful women, the patient men and patient women, the humble men and humble women, the charitable men and charitable women, the fasting men and fasting women, the men who guard their private parts and the women who do so, and the men who remember Allah often and the women who do so – for them Allah has prepared forgiveness and a great reward. [33:35]

This verse from Surah Ahzab is a good place to start in trying to find key virtues: belief, obedience, truthfulness, patience, humility, charity, abstinence and moderation, chastity, and mindfulness of God. I also began searching in the Quran to find the names of people who God is pleased with and who are successful. The most common names I found are:

مؤمنون Mu’minun- Those who believe

صابرون Sabirun- Those who are steadfast/patient

صالحون Salihun- Those who are righteous

مخلصون Mukhlisun- Those who are sincere

محصنون muhsinun- Those who are good-doers

متقون Mutaqun- Those who have taqwa (scrupulousness)

خشعون Khashi’un- Those who are humble

Who wouldn’t want to be among those whom the Creator is pleased with? Who wouldn’t want to be forgiven and receive a great reward from our Lord? I believe in the coherence of the Quran and the importance of coherence in our lives. This is why I think that it is important that we look beyond the laundry list approach and focus on the key virtues outlined in the Quran. These virtues can be guiding lights in determining our course of action, leading us to live richer, fuller and happier lives. This is why it is important to explore each of these terms, to consider how they can guide us not just to a moralistic life, but a virtuous life. Some of the explorations may lead to dead ends, but with patience, dialogue, and careful consideration, they may lead to something fruitful. I hope you join me in this journey, as my aim is to explore virtue in Islam in search of an ethical system.

References:

[1] http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/franklin-virtue.html

[2] http://www.islamic.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/Tazkiyyah/station_of_muraqabah.htm

[3] http://www.islamic.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/Tazkiyyah/four_poisons_of_the_heart.htm

[4] http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1882smiles.html

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-help

[6] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twelve-step_program

[7]http://personal.ecu.edu/mccartyr/ancient/athens/Socrates.htm

[8]http://philosophy.ucdavis.edu/mattey/phi143/stoaeth.htm

[9] http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/belief/2010/feb/23/ethics-citizenship-islam

Occasionally, I will get a request from someone I never met, but they are a friend of a friend on facebook or they follow my blog. Ignoring a request isn’t a personal thing, but in a way it is. But not in the sense that I don’t like you or you’re a bad person, or you’re unimportant. I just don’t know you, even though some of you may think you know me. You only know some of my thoughts, personal reflections, and tendency towards typos and bad grammar. Maybe you get my humor or maybe you don’t. Perhaps we have shared interests or similar views, but we don’t have a personal connection. Most of us haven’t had an extended exchange for me to feel much of resonance. I just don’t want you to think I’m giving you the cold shoulder. It’s nothing personal, but following my blog isn’t enough for me to allow someone access to more details about my life, so that I can be known without a person truly knowing me. We have to have some type of professional, personal, or or academic relationship before I add you my facebook friends or give you my personal contact.

Occasionally, I will get a request from someone I never met, but they are a friend of a friend on facebook or they follow my blog. Ignoring a request isn’t a personal thing, but in a way it is. But not in the sense that I don’t like you or you’re a bad person, or you’re unimportant. I just don’t know you, even though some of you may think you know me. You only know some of my thoughts, personal reflections, and tendency towards typos and bad grammar. Maybe you get my humor or maybe you don’t. Perhaps we have shared interests or similar views, but we don’t have a personal connection. Most of us haven’t had an extended exchange for me to feel much of resonance. I just don’t want you to think I’m giving you the cold shoulder. It’s nothing personal, but following my blog isn’t enough for me to allow someone access to more details about my life, so that I can be known without a person truly knowing me. We have to have some type of professional, personal, or or academic relationship before I add you my facebook friends or give you my personal contact.