—Image from ModDB

“Knowing a great deal is not the same as being smart; intelligence is not information alone but also judgment, the manner in which information is collected and used.” – Carl Sagan

The Muslim world possesses a wealth of knowledge, especially in regards devotional literature, theology, and jurisprudence, yet we have not transformed our knowledge into thoughtful and well-executed ways of addressing our most pressing needs. Muslim communities throughout the world face a plethora of problems: poverty, authoritarianism, civil war, neo-colonialism, occupation, sectarianism, sexual exploitation, corruption, social inequality, civil war, natural disasters, etc. Even American Muslims, who are largely shielded from these perils, are challenged. We face a number of issues: cronyism, crime, domestic violence, poverty, ineptly run institutions, sexism, tribalism, infighting, isolationism, Islamophobia, and an inability to address the needs of marginalized members of our community. The American Muslim community is increasingly literate, with unprecedented access to traditional scholarship and information. Islamic institutions of learning are filled to the brim. Although the American Muslim community is predominantly middle class and highly literate, we somehow still seem ill equipped and are stuck in a quagmire (Pew). We are unable to talk to each other, work together, and develop a common vision. That special something is missing and that something is Critical thinking.

As Muslims, the command to “seek knowledge” is almost like a mantra. But how often are we encouraged to think on a higher level, let alone think critically? This is especially important to think about considering how God speaks of comprehension and thinking in the Quran. Tafakkur تفكر is the reflexive form of the root فكر, which means to reflect, meditate cogitate, ponder, muse, speculate. Tafakkur means to reflect, meditate cogitate, ponder muse speculate revolve in one’s mind, think over, contemplate, and consider. It is mentioned in the Quran 17 times. In Surah A-Rum verse 8 Allah says:

Do they not contemplate within themselves? Allah has not created the heavens and the earth and what is between them except in truth and for a specified term. And indeed, many of the people, in [the matter of] the meeting with their Lord, are disbelievers. (Sahih International)

The word for “Intellect” is ‘Aql عقل, meaning sense, sentience, reason, understanding, comprehension, discernment, insight, rationality, mind, intellect, intelligence. The verb form that we will see commonly used in Qur’an is عقل to be endowed with (the faculty of) reason, be reasonable, have intelligence, to be in one’s senses, be conscious, to realize, comprehend, and understand. In the 49 references of the word in the Qur’an, God often speaks of the disbelievers who do not comprehend.

In Surah Baqarah verse 276, Allah says:

And when they meet those who believe, they say, “We have believed”; but when they are alone with one another, they say, “Do you talk to them about what Allah has revealed to you so they can argue with you about it before your Lord?” Then will you not reason? (Sahih international)

Another important Arabic word that corresponds to critical thinking is the word for logic, منطق which means the faculty of speech, manner of speech, eloquence, diction, enunciation, logic. All three terms, are important to consider when we think of critical thinking. And, I will discuss later, we will see how Muslim scholars employed critical thinking in their struggle to determine what God intended for us to do when an issue was not explicitly stated in the Quran or Hadith literature. Critical thinking implies:

- that there is a reason or purpose to the thinking, some problem to be solved or question to be answered.

- analysis, synthesis and evaluation of information (CTILAC)

Without these two, we were seriously hamstrung. While having the faculty for critical thinking, our community has either ignored its tradition of critical thinking or underdeveloped due to reactionary thinking. As a result, we are a bit hamstrung by our own intellectual deficiencies. I say this with all respect, because we have many knowledgeable people, but they are not good problem solvers and their analysis and evaluation of information is lacking.

As a result, we hit a number of roadblocks. Many Muslims see Islam as a monolith and try to impose their rigid and authoritarian models on others. Our leaders are unable to come up with solutions to problems that were never imagined by classical or early modern legal and religious scholars. Individuals with little experience in non-profit development or leadership, build institutions with little understanding of how to meet social needs. And lay members of our community lock horns in heated theological and juristic debates that take away from a sense of fellowship and coherent communities. Our communities are fragmented by endless polemics where labels and plastic words substitute for real engagement with our differences and our commonalities. All of these problems come about because critical thinking in Islamic studies and devotional education is not something that is valued within our community. Despite our undervaluing of it, there is a great need for critically thinking Muslims, from your average lay member of the community, leaders, and scholars.

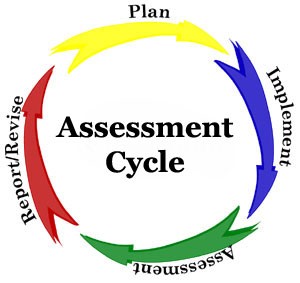

If we understand our own legacy of critical thinking and continue to develop critical thinking at all levels of devotional and Islamic education, Muslims will be better equipped to deal with our most daunting challenges. Before going into our legacy of critical thinking, it is important to understand how the term is currently used. The term “Critical Thinking” encompasses a wide array of ways of thinking and processing information. Scriven and Paul write, “Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action.” In my experience of teaching, from a high school to college level classes, the most important tool I have tried to help my students develop has been critical thinking. One of the best ways of seeing critical thinking in action was to have students write research papers with sound arguments. That is because “in essence, critical thinking is a disciplined manner of thought that a person uses to assess the validity of something (statements, news stories, arguments, research, etc.)” (Adsit). But I often found that most students lacked not only discipline and curiosity, but also an interest in developing their higher order thinking abilities. Instead, they often focused on trying to get the right answer, rather than learning to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information. When students don’t think well, they don’t write well. Writing is a higher order level of thinking, but anyone can write without thinking, just as someone can speak without thinking on a subject. But eloquent and logical speeches and well written papers reflect disciplined critical thinking. And both can be subject to critique by others who are keen to see logical fallacies, misuse of sources, or failure to include other factors.

Critical thinking is something that develops with practice. It is something we have to train for. Scriven and Paul write that critical thinking is a set of skills that help us “process and generate information and beliefs.” They also a “habit,” or inclination based on intellectual commitment, “of using those skills to guide behavior.” Critical thinking helps an individual recognize the following:

i. patterns and provides a way to use those patterns to solve a problem or answer a question

ii. errors in logic, reasoning, or the thought process

iii. what is irrelevant or extraneous information

iv. preconceptions, bias, values and the way that these affect our thinking. that these preconceptions and values mean that any inferences are within a certain context

v. ambiguity – that there may be more than one solution or more than one way to solve a problem.” (CTILAC)

Critical thinking is not limited to subjects, so religious thinking has also benefited from critical thinking and in fact, our own tradition of scholarship shines due to our classical medieval scholars’ commitment to critical thinking. One very insightful friend of mine reminded me that we go to college and pay for the skills that our classical scholars had developed. While people outside of the academy have natural inclinations towards certain aspects of critical thinking, often those skills are sharpened and refined during the process of learning a discipline. There is a stark difference between the ways someone like Suhaib Webb discusses a topic, drawing on his years of study and a lay member of the community. People recognize disciplines such as astrophysics and medicine, but often experts on subjects involving in the human experience are not as respected. And people will delve into these subjects without the requisite critical skills or mental rigor to truly engage with them. I found this out as I went into graduate school and developed my field of expertise on Islam in Africa and African History. Friends and family members would discuss a subject and if somehow my view did not agree with theirs and I explained my stance, I would experience their resentment. I learned to be quiet for the sake of peace, even if a loved one was speaking on an issue they were largely ignorant about. Our own willful ignorance in our community is especially detrimental to developing critical thinking. This is especially the case in terms of how some groups of Muslims overlook the 1400 year legacy of critical thinking and scholarship that has allowed our tradition to maintain continuity without a central body or leader to guide it.

Before I took my first course on Fiqh (Islamic Jurisprudents) at Zaytuna in the late 90s, I had no idea about the rich legacy of critical thinking in Islam. I learned about the skills qualified jurists needed to draw on the Quran, Sunna (Prophetic traditions), scholarly consensus, and qiyas (analogy) to come up with rulings on new issues. That basic class whet my appetite on the study of Usul al-Fiqh (Sources of Islamic Jurisprudence), which I later studied a bit in graduate school. Usul al-Fiqh is concerned with the source of Islamic law and methodology in which legal rules are deduced. Kamali explains that the process by which scholars use to deduce sources to try to understand Shariah, Holy Law, is ijtihad. (1). The rules of fiqh use various methods of reasoning, including “analogy (qiyas), juristic preference (istihsan), presumption of continuity (istishab), and rules of interpretations and deduction.” In essence, Kamali points out that Usul al-Fiqh provides standard criteria for deriving correct rulings from the sources (2). However this standard of criteria is now overlooked by many who use ijtihad to come up with convenient rules that can lead to one of two extremes: ultra-liberal positions based on Western inclinations and not on Quran and Sunnah or ultra-conservative positions that purport to be derived strictly from Quran and Sunnah but violate the spirit of Islam.

Before delving further into this discussion, I must admit that I feel woefully ill equipped to engage in any Usuli debate on some religious issue. However, I find that many Muslims will become locked into debates that were never solved by our most gifted jurists. Often lay Muslims, with access to translations of the Quran and volumes of hadith, in addition to treatises and polemics, will derive their own rulings on religious matters based on their understanding of a Quranic verse or a hadith. According to Kamali, historically “the need for methodology became apparent when unqualified persons attempt to carry out ijtihad, and the risk of error and confusion in the development of Shari‘ah became a source of anxiety for the ‘ulama” (4). As a champion of inquiry and free thinking, it is difficult for me to openly admit that I understand their anxiety. But the reality is that our community is struggling with a crisis of authority, and that is mainly who has the authoritative voice in interpreting Islamic law.

The independent, thinking Muslim may feel like he/she is engaging in critical thinking when approaching the highest sources. However, a critical piece is missing. Ebrahim Moosa writes “… untrained in the various exegetical and interpretive traditions, lay people are not aware that a complex methodology is applicable to materials dealing with law, even if these are stated in the revelation” (121). Most lay Muslims are not trained in the language or historical context to know whether a verse was a commandment to a specific group of people at a specific time or to all Muslims of all times. Nor do they always know whether a verse was simply a statement of fact at a historical moment. Similarly, Muslims will use a statement of the Prophet (s.a.w.) without any context or understanding if it was a religious injunction and apply it to their lives. While ignoring aspects of that scholastic tradition, they will draw on it to reject a hadith and say it is da’if (weak). Or they might draw on the polemical writings of a classical author to dismiss the ideas of another tradition. Yet, they often draw on these traditions in sloppy ways that result in more confusion. Sadly, this is because many of the polemical books were written, not for lay people, but for other people who have the requisite skills and training in evaluating and analyzing sources and discipline in reason and logic.

This does not mean that a lay member of the community solely rely upon someone else’s critical thinking, rather that we recognize our own limitations in our knowledge and training and leave open some room for ambiguity. Perhaps we shouldn’t be so willing to condemn others if we don’t have the skills to even assess the validity of their stances. This requires humility which many, me included, often lack. Humility is an important part of sincerity, which is an important component of purifying our intentions before going about any endeavor. When I first converted to Islam and read my few dozen books, I felt a lot more sound in my knowledge than I do now. I didn’t know how much I didn’t know or my deficiencies in training. The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don’t know. The less arrogant I feel about my own knowledge and the more in awe I feel of those scholars who wrote without laptops and cut and paste. Even as we have unprecedented levels of literacy in our community, we must fight narrow mindedness and gathering up of information without being able to judge and assess or use that information for the greater good. And through developing our critical thinking, that Islam is more expansive, rather than restrictive and reactionary. Our greater comprehension through this intellectual struggle will be a truly enriching and humbling experience.

[Note: In order to keep this article digestible, I will continue to develop the themes in later posts to explore other aspects of critical thinking in our community. So, please consider this a part 1 of a longer series. ]

References

Adsit, Karen I. “Teaching Critical Thinking Skills”

http://academic.udayton.edu/legaled/ctskills/ctskills01.htm

retrieved August 13, 2011

CTILAC Faculty Critical Thinking & Information Literacy Across the Curriculum http://bellevuecollege.edu/lmc/ilac/critdef.htm11/18/98. Retrieved from Internet August 13, 2011

Foundation for Critical Thinking “Critical Thinking Professional Development for K-12” http://www.criticalthinking.org/professionalDev/k12.cfm

retrieved from the internet August 20, 2011

Kamali, Mohammad Hashim. Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence. Islamic Texts Society, Cambridge, UK, 2003

Moosa, Ebrahim. “The Debts and Burdens of Critical Islam” Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender, and Pluralism. One World Publication, 2003

Pew Research. “Muslim Americans: Middle Class and Mostly Mainstream.” May 22, 2007

The Quran: Sahih International Almunatada Alislami; Abul Qasim Publishing House http://quran.com

Scriven, Michael and Paul, Richard. “A Working Definition of critical thinking by Michael Scriven and Richard Paul” http://lonestar.texas.net/~mseifert/crit2.html

Retrieved August 10, 2010